|

| There are no photos of the Ju 290 A-9 but Spain's single bird post war looks very similar. |

If you've ever read anything about the Junkers 290, you've probably come across mentions that at some point there were flights to Manchuria. Given the Ju 290's capabilities, and its close connections with German Intelligence and the senior leadership of Hitler's Germany, the Ju 290 was a natural choice for these routes to Japan. Books about World War 2 aviation frequently assert that these flights happened, though details are often sketchy. The mentions of these flights are not just obscure nerd-lore either; even Albert Speer in his "Inside the Third Reich" mentions offhand that these flights were taking place. If you do a bit of digging around on the subject, (as I did) you discover three things:

1. The Nazis had three different types of aircraft capable of making the flight, and all could carry cargo loads while doing it;

2. The Germans had a fair bit of interest in making these flights, and studied the possibility of doing them throughout the war. They also (through KG 200) set up a "kommando Japan" for making these flights, and even had three Ju 290s constructed specifically for this mission, the Ju 290 A-9;

3. The Axis also had motive to attempt these flights - after the invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, lines of communication with Japan were virtually cut off, and the only other viable way of sending personnel, plans, and cargo was via submarine, which left a lot to be desired.

So, flights to Japan have a plausibility that the other unconfirmed Ju 290 rumors simply can't touch. The question again, then, is did these flights actually happen? Short answer: no. But the story of why they didn't happen, and how so many sources got the idea that they did, is a story worth telling.

VIII: A Short History of Quinine Smuggling by Submarine

I've already written about the Ju 290's involvement in air dropping agents into Iraq, flying Nazi war plunder to banks in Switzerland, and even with its involvement in possibly flying Hitler to Spain. I now have to double down on these lurid plot-lines by introducing Submarines carrying literal tons of gold to pay for German wunder-waffen.

The trade relationship between Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan was at root very simple. Germany wanted resources from Japan, particularly rubber, and metals like Chromium and Vanadium, which are used in the forging of high quality steel. Japan in return wanted patents, plans and technical assistance from Germany. Japan had transitioned from a essentially medieval to mostly modern industrial society in about 50 years, and in that time had learned to love the licensing of foreign technology and patents. Just in my own personal Luftwaffe posts, the Japanese have shown up. The first combat Fw 200 was almost sent to Japan; Heinkel sold two He 119s to the Japanese, and the Junkers G38 was built under license by Kawasaki as a heavy bomber. The Ju 290 was also to have been acquired - it was planned that three Ju 290s, built as heavy bombers, would be flown to Japan in case the Japanese managed to crack the whole 'atomic bomb' problem.

This exchange was easy in peacetime, and continued when war broke out in 1939 - trade happened by the trans-Siberian railway. This trade route was brought to (possibly literal) screeching halt, of course, when Germany attacked the USSR in June 1941 - and if you are ever compiling a list of all the ways the Nazi attack on the Soviets was stupid, "making trade with our ally in the east impossible" should be somewhere down there.

Once it became clear that the Soviets were still standing at the end of 1941, some thought was given to resuming trade with Japan. The only option available to the Axis was trade via cargo carrying submarine. Japan, luckily, was well equipped for this: its submarines had been designed for trans-Pacific cruising, and were both large and had a exceptionally long range. Many Japanese subs were also equipped with scout aircraft hangers, which was easy to convert for cargo carrying. It's here that the advantages of the plan ran out. For one, this would obviously be a low-frequency endeavor with a very low capacity for cargo or personnel. Second, as the Axis discovered, it would be very risky. In a sunnier, more fascist-friendly world, this surreptitious trade route would have gone unnoticed by the Allies; as it was, Allied signals intelligence had broken Axis diplomatic codes, and were well on their way to breaking the Enigma cypher. As soon as one of these submarines embarked, it was made a high-priority target by Allied Navies. One of these submarines, the I-29, was attacked three times in her approach to and departure from the U-boat pens in France. She managed to make it back to Singapore and offloaded her passengers, but not her cargo. Sailing back to Japan, she was intercepted a fourth time by a American task force of three submarines formed specifically to sink her. The Sawfish torpedoed her, and her cargo was sent to the bottom.

|

| I-29 arrives at Breast. |

IX: Siberia Clippers

Given that history, you can understand why the Germans and the Japanese immediately started to seriously look at flights from Europe to the far east to supplement submarine-based communication.

Intelligence cables between Tokyo and Berlin begin talking about the possibility of flights to Japanese occupied China in May 1941. These cables go on to say that Hermann Goering and Lufthansa had both studied the issue by spring 1942, but both had come to the conclusion that the technical problems were just too great for any flights to take place. There was another issue, as well. The Japanese, in 1940 when they entered into the Tripartite pact, had been mulling their options in the expansion of their empire. Given their forces, they had two choices: attack the USSR in West Siberia, or to attack Indonesia and the Philippines, meaning war with the United States and Great Britain. The Japanese decided the latter move was the smart one: the European and American imperial holdings had all the resources Japan's economy craved, and the Soviets had proven very competent opponents in a border war with Japan in 1938. To secure peace with the Soviets, the Japanese then signed a 5 year non-aggression pact with them. Once this was done, the only Japanese interest in the USSR was maintaining the peace, and Japanese diplomats fretted that any overflights from Germany to Japan would be used as a pretext by the Soviets to nullify the treaty.

The Germans also spent a fair bit of time distracted. The war between the USSR and the Nazis started with Hitler convinced that the war would be over in six months. Then, mid 1942 saw that crisis in German air transport that the previous post mentioned; this crisis didn't really abate completely until Germany was defeated in North Africa in May 1943. With every single freight haulin' airframe needed, there was not much time to consider a flight to Japan. (There was also the usual attitude at work with submarine transport - a 'wait and see if it is good enough' approach that the Nazis frequently assumed.) So it was only in later 1943 that the question was taken up seriously again. Another factor in the resurgence of interest was no doubt the existence of the Ju 290 - by later 1943 it was both in production and proven itself mechanically sound.

Still, in late 1943, the Nazis suddenly realized that these flights would be worth doing, and (credit where credit is due) they made up for lost time. Milnch chaired a high level meeting where options in aircraft and routes were reviewed. The Ju 290 was picked as the aircraft as it was the most modern of the existent airframes, and had better production possibilities than the other contender, the colossal BV 222 flying boat. What loads could be carried is extremely difficult to say, but at least 5-6 tons seems plausible for the Ju 290.

Possible routes for these flights were also studied:

1. The Northern Route. Flying from Kirkenes at the extreme northern tip of Norway, or possibly from the north of Germany's wavering ally Finland, the Northern route was the clear favorite. On a great circle arc, the flight would avoid the populated parts of the Soviet Union entirely, flying down through the especially empty parts of Siberia to Manchuria. The total distance depended on the destination. Baotou was less than 5000 km:

Where a route to Northern Manchuria was 5500:

And a flight to Sarkel Island was 6000 km, with a flight direct to Sapporo being 6300 km.

Any of these routes were possible with the Ju 290 A-9.

2. The Southern Route. Flying from Odessa in the Ukraine, a flight could aim for Japanese-occupied inner Mongolia. Flying a little north of Stalingrad and skimming the top of Kazakhstan, the route was 6200 km, and spent nearly all its time over Soviet territory. Even in late 1943, the prospects for this route were in decline. Any of these flights would have to fly across an active war zone, and the possibility of even using Odessa as a staging area looked more and more unlikely.

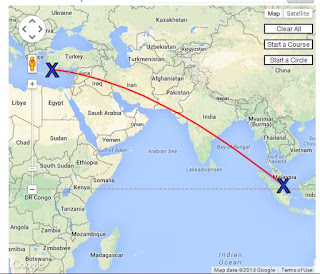

3. The "Politically Acceptable to our Allies" route. The Japanese since 1942 had been proposing an alternate route route that avoided the Soviet Union entirely. Starting on the island of Rhodes, it went over Iraq, Iran, and right across India to the Bay of Bengal down to Singapore. The route was both the longest, (8000 km to Rangoon, 8700 km to Singapore,) and the most dangerous, spending most of that distance crossing Allied territories. This route does not seem to have been taken too seriously, both because of the risk of observation and interception, and the difficulties of doing anything out of Rhodes, now cut off from Axis supply lines.

The Ju 290 in Maritime Recon form had a range of 6000 km, and the BV 222 had a range of 7000 km as a patrol plane. Maybe more importantly, these aircraft had plenty of space for extra internal fuel tanks, while retaining some cargo capacity. The result of this meeting was the commissioning of three Ju 290 A-9s. As I've already said, the A-9 had no defensive guns, but kept the maritime scout fuel tanks, and had internal fuel tanks added. The A-9 was finished in bare metal as well, to save weight and limit drag. These three aircraft took to the sky in January 1944, and the mods paid off: the range of the A-9 was calculated to be 9000 km loaded, enough to make the flight and have a 10% fuel reserve. These three aircraft were assigned to KG 200.

And here we come to the anticlimactic part of the story: the Germans were ready to attempt these flights in early 1944, having the crews, the will, and the aircraft to do it. But the Japanese still would not give permission to overfly the USSR. The three A-9s went on to serve with other Ju 290s as spy-droppers on the eastern front, with all being lost in 1944; two to enemy action, and one written off in a bad landing at a German airbase. Then, the fighter emergency program ended production of the Ju 290 and the BV 222. With this, flights to the far east and back appear to have been forgotten about.

In hindsight, this caution on the part of the Japanese seems rather foolish since it didn't save them from the Soviets. After Germany surrendered in May 1945, the Soviets agreed to enter the Pacific war within three months, and did so with gusto, invading Outer Mongolia with a two million man army in August 1945. If they had wanted to demoralize the Japanese, they could not have picked a better date; the day of the attack was the same day as the atomic bombing at Nagasaki.

That said, the Japanese worries were not entirely baseless - they had been burned before. By Italy.

X: Italy is to Blame

I've already stated that German flights to Manchuria did not happen. I was surprised to learn that the Italians, however, managed to do it once.

If you were an Italian Fascist in 1942, you had reason to be down. Italy, for all of her ambitions, had become the Fascist little brother of the Axis who always needed Germany to bail him out of scrapes. So, when the chance came to get a little prestige with her allies, it's not surprising that Italy approached it with a can-do spirit.

The Savoia-Marchetti SM.75 Marsupiale (Marsupial) was a airliner/transport developed in the late 1930s. A smidge larger than the Douglas DC-3, the SM.75 can be thought of as Italy's Fw 200 - a civilian aircraft drafted into World War 2. Also like the Condor, the SM. 75 was modified to give great range. These aircraft first served as overseas airliners to South America, and as a way of maintaining communications with Italian colonial possessions in Abyssinia and Eteria. As 1942 started and the Soviets remained undefeated, the Italians started to plan a flight to Manchuria. The SM. 75 was modified to create the SM.75 GA (Grande Autonomia, or long range.) This aircraft could fly 7000 km with a two ton payload with a crew of five, or 9000 km with no payload (presumably still with a crew of five.)

Once plans were laid, the first SM. 75 GA first flew a long distance test flight. In January 1942, a SM.75 GA took off from Bengazai and flew to the now British-occupied Abyssinia, to drop propaganda leaflets to Italian settlers there. It was then supposed to return to Benghazi, but the pilot decided to fly to Rome instead, arriving safely after 28 hours in the air. The flight to Tokyo was now planned. A second SM. 75 GA was constructed and was made an extra-special edition with the addition of two extra letters: RT, or Rome-Tokyo. The SM.75 GA/RT took off from Guidonia Italy, on June 29th 1942, bound for the Ukraine. On board were new diplomatic cyphers for the Japanese, and a new German naval attache for the German Embassy in Tokyo. The destination was Zaporizhia, a Ukrainian city captured by Axis forces in the 1942 offensive, just north of Rostov. Italian engineers had constructed a airstrip and radio base to support the Tokyo attempt. Once here, the SM.75's fuel tanks were topped off and the SM.75 departed the next day for Manchuria.

It was a difficult flight. The SM. 75 GA/RT was so loaded with fuel initially it could not climb past 2500 ft. It of course was also for some distance flying over a active war zone, and was fired on many times by Soviet Flak. It was also stalked for a time by a single Red Air Force fighter. Even a superficial hit on the SM.75 could have meant disaster, since the Italian aircraft had no self-sealing fuel tanks. While the battle of Rostov still active to the south, the SM.75 flew over Russian steppe, Kazakhstan and the Gobi desert. As expected, Russian-sourced maps proved inaccurate for most of the trip, so the Italians had the foresight to make Dr. Publio Magini the navigator and co-pilot. Italy's most experienced long distance pilot, Dr. Magini had also invented a method of navigation using "star altitude curves" which apparently was of use on these flights. After flying some 5500 km, the city of Baotou in Inner Mongolia was reached. It had been chosen as the point for the intrepid flyers to land both for its relative nearness to Europe and its comparative remoteness from everywhere else - the Japanese were still intensely concerned about the Soviets hearing about the flight.

|

| The SM.75 in Japan. |

After the end is oddly where things went wrong. The Japanese wanted the whole flight kept quiet, but soon the story was in Italian newspapers. It's not clear if this was an accident or a little leaking on the part of Italian Fascists, but Japan quickly decided that its Gaijin allies lacked the discretion to pull off operations like this without making a whole lot of Gaijin-y self-triumphant noise, and would never again agree to one of these missions. Japan soon proposed the bordering-on-impossible Bengali route as the preferred way to fly to the Far East, and Italy soon gave up on the idea of repeating the flight.

Anyway, that's the end of the real history of the subject. So, where did this notion that these flight were made come from?

XI: The Ghost of Evidence*

The evidence for these flights taking place is rather thin. There are scattered references to it in allied intelligence sources, all of them reports on German POWs mentioning these flights. The main account of these flights comes from one of these POWs.

Wolf Baumgut was a pilot in the FAGr 5 recon group from its formation to April 1944.. When captured, he was eager to tell all to Allied intelligence. This produced a report dated Mar 29th, 1945 – “FAG(sic) 5 over Manchuria.” According to Baumgut, he had been taken out of the line in February 1944 and sent with three FAGr 5 Ju 290s to eastern Germany, where the planes were modified in 48 hours with internal fuel tanks. They also had their external weapons removed save the tail turret, and any armor that could be easily removed. Baumgut then made two flights to the far east: the first time departing from Odessa to Manchuria, returning to the Reich via Milec, a Polish town. The second and third flight departed and returned from Milec. The crew was just three – Baumgut as the radio operator, a co-pilot, and a man in charge of flying and navigation. He wore a blue uniform without insignia, and had a glass eye – even the intelligence report referred to this man as “the mysterious observer.” Cargo from the Reich was a large crate labeled “Secret – Handle Carefully” and the latest BMW 801 radial aircraft engine. The cargo on the return trip the first time was various metals weighing in total 8 tons; the second trip returned with 6 tons of raw rubber. Baumgut also claimed that the other two modified Ju 290s made one trip each, departing from and returning to Posen, another Polish town.

While this story hangs together well in the history we've already covered, it has a few problems. The aviation historian Kenneth Werrell has pointed out that many details of the flight - particuarly in flight time, speed, and navigation don't appear especially sensical. (I've uploaded his paper to scribed if you want to get into the details.) There's also the question of why three more Ju 290s would be modified when the A-9s already existed and had done flight tests. But let's cut to the chase as to the problem of Baumgut story: the deafening silence of any other source corroborating this tale. This would be damning in most circumstances, and is especially damning here, as this was high-level strategic co-operation between two allies at war. Not only would have the Luftwaffe been involved, but the Nazi and Japanese diplomatic apparatus would have been involved as well. Presumably, the same procedure that involved cargo submarines would have been used for cargo planes, and that meant diplomatic communications being sent by cyphers the Allies could read. So in addition to Japan and Germany, the Allies would have had a paper trail as well. Given how thoroughly compromised secret Axis communications were by this time, not having any records of this flight (when the Sub cargo runs, before and after, have extensive records) is especially telling against the story, even more so when you consider that there were five succsessful flights on Baumgut's account, and not just one. Even the Allied interrogator who wrote the report was skeptical, noting that Baumgut was eager to please his new friends, and that his stories (for there is more than one - he was also the source for the myth of the New York recon flight we'll be looking at next time) should be taken with a grain of salt.

Despite the fact that the story was literally just a story without any evidence to back it up, it managed to enter and remain in circulation, as it was both plausible and interesting. How it comes down to us today is so many otherwise credible sources have repeated it. There are two pictorial-monograph type modeller's references on the Ju 290 in English: Monogram Close-Up No.3: Junkers 290 and Heinz Norwa's evocatively titled Ju 290, 390 etc., and both repeat the myth. The Putnam edition of German Aircraft of the Second World War has the myth of the far east flight. This book in particular saw wide circulation, with many reprintings - it also became a preferred source for Wikipedia editors being both 1) completely online, and 2) free , and thus can be cited by a whole new generation of airplane nerds. A historian in the 1980s, Janus Piekalkiewicz, in his The Air War: 1939-1945 tells a similar story to the Baumgut tale - without any references or sources. In America, William Green's Warplanes of the Third Reich went through many reprintings, and has the Far East flight myth as well as the Myth of the New York Flight. (In Green's defense, he since decided that both flights didn't have any evidence to back up the stories, and are quite likely untrue.)

There are of course people who still defend the myth, and I can have a little sympathy for them since it is, after all, possible. They usually try to argue away the complete lack of records for a far east flight with a few stratagems. The most common is to suggest the flights did happen, but with a Lufthansa crew, or in airplanes in Lufthansa colors, or both. It is true that the British, for example, used ostensibly civilian aircraft for intelligence work - the OSS and British Intelligence had many aircraft that were nominally BOAC aircraft flying to Sweden, and the neutrality of airliners flying from neutral countries was (somewhat) respected by the Germans. That doesn't make Lufthansa Ju 290s in the far east any more plausible, however. First, legitimate flights from neutral countries to belligerent ones were made possible by cooperation on both sides of the war - small agreements were made to respect airliner flights from Lisbon to England, for example. Second, these flights were not taking place over hostile airspace, where flights to the Far East would explictly have to. The view that a *civillian* German aircraft over West Siberia would be viewed with less hostility by the USSR shows an almost adorable naivete about the war on the eastern front. It also must be said that any German aircraft somehow detected flying to, from, or in the far east would instantly raise suspicions that Japan and Germany were engaged in trade. These were flights that could only rely on complete secrecy to be viable - the aircraft involved would have no defenses, and no plausible cover if they were discovered.

If the idea is to explain away the complete lack of evidence in archives for this flight, it doesn't really work either. Even if you assume for a moment that letting a nominally civilian outfit handle things would keep records out of military archives, there would still be fairly extensive documentary evidence elsewhere in the Nazi hierarchy, starting with the RLM (Reich Air Ministry) and involving German diplomats at a bare minimum. And these are just paper records; considering how many war atrocities the Nazis tried to cover up and failed, it would be quite singular if nobody came forward post war with the stories of these incredible flights, had they happened. Then, there would be records (and people) on the Japanese side. And of course once these two nations communicated their mutual plans to each other over wireless, the Allies would have records of the operation as well.

So, yeah, the evidence is very, very, weak for these flights taking place. While they remain technically possible, several aerospace historians, some specialized in German aviation, have looked for evidence for these flights, and come up with precisely nothing. So barring some grand new revelation, we have to conclude these flights never happened.

|

| A Ju 290 - the Roundel on the wing might be the Spanish one - with a B-25 and a squadron of Bf 109s. |

Special thanks to my good friend Diana who risked much to bring that Warrell paper to me through a university interlibrary loan system. Mad props, yo, should also be given to acscdg.com for easy to use circle mapping tools, and comandosupremo.com for the story of the SM.75's surprising flight.

Other Ju 290 posts

Part 1: Actual History

Part 3: Fake History