|

| A He 177 starts up; note the man in the foreground ready with the fire extinguisher. |

1941 must have been a good year to be a Nazi. Everything was coming up Hitler! The French were beaten. The Third Reich has expanded its borders greatly, having become the hegemon of Continental Europe. Their remaining opponents, the British, were locked out of the continent entirely. What's more, Germany was so strong in Europe that the war's center of gravity had shifted to the Mediterranean, away from the Reich itself.

Our story picks up at the start of 1941, when all the big garbagemenchen were fresh back from jew-free Christmas. Hitler had made the monumental and ultimately fatal decision to attack the Soviet Union - the Third Reich was pivoting to the east. While the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe had been given the job of neutralising Britain, most Luftwaffe units in France and the Low Countries had been reassigned, leaving a small force to coordinate with the Kriegsmarine's U-boat campaign.

The Kriegsmarine, though, was still feeling optimistic, as it made a request to the RLM for something. While the German Navy didn't have many aircraft to support its U-boats with, it did apparently have some optimism that the He 177 or some variant of the Bomber B project would be deployed in the near future. (The 'Bomber B' project - the He 177 was procured under the 'Bomber A' project - was an ambitious Nazi effort to replace its current medium bombers [the Ju 88, He 111, and Do 217] with much higher performing next generation models. The key to all these designs was the Jumo 222 or the Damiler-Benz 604, engines projected to make 2500 hp with similarly advanced drag characteristics and power-to-weight ratios. Both engine programs ended in failure, and so all the Bomber B projects would be cancelled.) What the Kreigsmarine wanted, in the spirit of sunshine, was a bomber to support the Kriegsmarine in the Western Atlantic. While the goal of the Kriegsmarine was reconnaissance for U-boats, this request was perhaps inevitably bundled in with the Amerika bomber program, which had suddenly found high level interest.

Back to the Batcave

This was because in the new year, Herr Hitler himself checked in on the subject, and said that developing bombers with a 12,000 km range was of vital importance for eventual strategic raids against American Industry. (I invite readers to imagine how big an aircraft with a 40% greater range than the B-36 would be.) There was a certain logic to the request; the longer the range of the Amerika bomber, the more of America could be threatened with small attacks. An aircraft possessing that range, taking off from France or Northern Scandinavia could cover the entirety of the United States. At the same time, Hitler's views on Germany's ability to construct an Amerika bomber were a bit...askew. While work on prototype aircraft was of course possible, Hitler seemed to think such an airplane could have become minimally operational in 1941, which was hilariously impossible. Further, the construction of such aircraft beyond small numbers was impossible for the Reich unless they expanded their manufacturing base considerably (with the attendant increase of resources) or took large resources away from some other aviation sector and applied it toward Amerika bombers - another impossibility. Hitler was of course planning to do the former - but to do this, he was going to risk all and try and conquer the Soviet Union. Even if this went well, it meant the biggest military campaign in modern history, with attendant strains on Germany's already tapped out industrial base.

Hitler in 1941 actually made mention of attacking America with aircraft several times. In April 1941, Hitler told Japan's ambassador that the Nazis would "carry through an energetic struggle by U-boats and by the Luftwaffe against targets in the USA. [...] The American Republic would have to be dealt with severely." In addition to damaging American industrial output, Hitler being Hitler naturally was enthralled with the idea of New York City 'going down in a sea of flames' with skyscrapers as gigantic 'towers of flame' eventually collapsing upon themselves. Hitler contemplated during some Nazi symposium in 1941 the usefulness of acquiring the Azores or the Canary Islands for use as staging areas for air attacks against America. Hitler also said to Mussolini that by the end of 1941, the Luftwaffe would have a Messerschmitt bomber for attacking North America with.

While the RLM did not issue Hitler's design requirement, they did issue a new tender for an aircraft that had a 6000 km range, with a reserve of 1500 km, capable of carrying 3-5 metric tons of bombs. This was the range needed to fly from France to New York City and back again. The tender emphasized "rapid development."

Arado

Arado, one of the German Aeronautical industry's smaller players, responded to these surprising developments with a hell of a concept: the Ar E470.

They saw the various demands that Nazis wanted this hypothetical air-frame to do, mixed them all together with an admirable "fuck it, let's do it live" attitude, and got the idea in circulation in spring 1941. The E470 was both huge and unorthodox: it was a sort-of flying wing design, with a wingspan of 68.5 m (224 ft) and a split boom tail, like the P-38 Lightning. The cockpit was pressurized (Arado had already built a aircraft with pressurization, the Ar 240) and the aircraft was projected to have a max takeoff weight of 130 metric tons, twice that of the Boeing B-29 Superfortress. The bomb load was the specified 5 metric tons (11,200 lbs), with a range of 7400 kilometers. Like many other big Nazi designs, the E470 also had the option for four or six engines, depending on what was available. The desired engines were DB 613-9s making 3500 hp each.

But wait, there's more! The E470 came with several model variants, with an emphasis on ultra-long range bombing or shorter range naval reconnaissance/attack. The most interesting detail was the option to turn any of these aircraft into a transport by bolting on a 30 ton external cargo pod. The E470 had tricycle landing gear, and Arado engineers pictured a removable shipping container being attached beneath the bomb bay. As if all this was not enough, Arado said the aircraft would take a crew of four, with the navigator/radio operator/engineer (however you want to split that up) manning the series of defensive turrets remotely.

The RLM declined the project in the end of 1941, but I'd like to think Arado got a golden swastika on their final report for the effort.

Blohm und Voss

Blohm und Voss found itself in a good position in some respects: with the experience it had gotten with the development of the BnV 222, the development of the new BnV 238 was going about as smoothly as it was possible for a Third Reich aerospace project to go. While the Reich had declined to get experience with strategic bombers and were now paying for it, they somehow did manage to snag "how to build large flying boats."

Though not a lot of large flying boats. The sum total of BnV 222 production to the end of 1941 would be three. It was less a production in any recognizable sense and more of an extremely slow production of prototypes. The BnV 222s were used a far-behind-the-lines transports, a job they were admittedly quite good at.

Dornier: The Death of a Whale

The Third Reich, as you may understand by now, was not very well organized.

Consider large flying boats. The Nazis developed the BV 222 with no thought of military applications. Then, in 1940, they commission Blohm und Voss to build a new, properly militarized flying boat, the BV 238. Meanwhile, Dornier has spent a lot of time militarizing their giant civilian design, the Do 214. But it was only after Dornier erected 12 giant building frames for series production that the RLM got back to them with a

about the project.

There were good reasons for this. The BV 238 had similar speed and range projections to the Dornier 214, even though the Do 214 weighted some 50 tons more. Another fly in the ointment was that the RLM now reckoned - despite efforts by Blohm und Voss - that the BV 238's defensive guns would be still insufficient to defend itself alone over the Atlantic. The Do 214 was obviously more vulnerable, still. And, of course, engines. The 2000 plus horsepower motors envisioned by Dornier were not available, and so as a interim choice, the engines slated for the Do 214 became DB 603s with roughly half the power. This cast the shadow of doubt over the entire project, as things like range and payload (not to mention how slow and vulnerable such an airplane would be) were reliant on engines. So Dornier, after a lot of work, was out of luck. They would attempt to salvage some of the project by cutting down the 214 into something more focused; this project would eventually be known as the Do 216.

Focke-Wulf

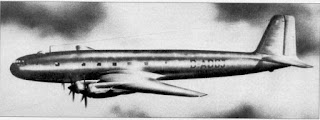

|

| The Fw 300 bore a resemblance to the C-46 Commando. |

The Fw 300 was the most natural of these; a successor to the Fw 200. This is where the logic to Focke-Wulf's plan ends, however. The Fw 300 was pictured as being a larger, more capable aircraft with trans-Atlantic capability and full pressurization - but it was also pictured as a civilian airliner. I guess due to optimism, the Fw 300 was going to follow the path of the Fw 200, and be a civilian aircraft first, and then be modified into a military specification. As an afterthought, the plans for the Fw 300 included a military version, envisioning some sort of western/central Atlantic prowling capability with standoff weapons. Focke-Wulf, unfortunately, had no capacity even for the design work for this project, so it was subcontracted out to SNCASO in France. Not surprisingly, not much was heard after that, though design work on the Fw 300 was being done as late as 1944. It is likely that Focke-Wulf choose this odd approach as they felt they had other horses in the race: they had their own 'Bomber B' project, the Fw 191, and this had provisions for a conventional four engine version.

Focke-Wulf around this time started a steady stream of project proposals that would eventually lead to the Ta 400, but trying to track the projects that lead up to this is more than a little confusing, especially as Focke-Wulf would frequently jump the gun and make up designations, which was strictly the RLM's privilege. They were all tightly focused on a low drag configuration of four to six engines that looked very similar to the Boeing B-29, abet with a split tail. These ruminations started in 1941, and aimed for Amerika bomber range.

The first of these Focke-Wulf called the Fw 238. The most unusual thing about it is that it tried to use non-strategic war materials, IE wood and steel, for its construction. The fuselage would have to been made out of wood, with structural hard points using steel. It used BMW 803 radials for propulsion - another entry in the big book of linked together aircraft engines. In this case, two BMW 801 radials were linked together and liquid cooled to create an engine with a theoretical output of 3,800 hp. In this application, Focke-Wulf detuned them to a more sedate 2,200 hp. The engines drove a pair of contra-rotating propellers. The crew of six was pictured being all located in the pressurized cockpit, operating remote defensive turrets. It managed to be somewhat smaller than some proposed Amerika bombers - it had a wingspan of 50 m (164 ft) and a length of 30 m (97 ft). That makes it closer to the B-29 in size, rather than the B-36. It had a range of anywhere from 8-10,000 km, depending on engine, and could carry the requisite 5 metric ton bomb load.

While a good initial effort, the project ran into serious problems immediately. The wood structure might have worked brilliantly on the de Havilland Albatross, but making such a heavily loaded aircraft structurally sound with wood was apparently nightmarish. Even with the wood construction, to meet the payload requirements of fuel and ordinance required shaving the safety load factor very fine - possibly too fine, even for the Luftwaffe. The BMW engines were vaporware and substituting in production power plants was in many ways, er, not optimal, and the remote turrets (as is tradition in these designs) just didn't work, causing a frank reappraisal of the project, and a rollover to a new designation.

|

| Still unavailable. |

Unlike most other aircraft manufacturers, Heinkel was knee-deep in the dead in a large bomber project. This might have been a good thing, but the project by this point was a dumpster fire that showed no signs of being extinguished.

The original target date for operational deployment of the He 177 was fall 1941, but that goal looked increasingly doubtful. What was more discouraging was the Kommando Rowehl [the test center for high altitude flight] had released a report in May 1941 that the He 177 was 'unsuited to combat operations' and that a conventional four engine configuration was now favored. Heinkel began designing two variants with four engines - the He 177B, a straight four engine version, and the He 274, a redesign of the He 177 with four engines for high altitude operations. At this point, decisive leadership from the the RLM could have gotten the program moving again, but it was singularly lacking at this juncture. He 177 would stumble on, while the development of the two substitute aircraft could only progress so far without state backing. The RLM now in 1941 viewed the He 177 as one of its most important projects, and didn't want to cancel it despite how badly the flight tests were going without a "firm date" as to when Heinkel's proposed successors could enter service.

The He 177 got pulled into the discussion of extremely long-range bombing - but the heavy bomber, er, weighed a lot, and didn't have the range, even if the engines were assumed to be sound. This lead to a discussion as to what mid-air refueling could do for the Third Reich. Assuming you could refuel the He 177 in the air, you could kill two birds with one stone: you'd then have a bomber developed for long range attacks that stood a reasonable chance to defend itself over a target. Looking back on it, this was a breakthrough in military flight; in the postwar world, everyone quickly realized the importance of aerial refueling, as it allowed you to get around many of the problems the Germans and the Americans faced with ocean spanning super bombers. Fieseler (makers of the Fieseler Stork) were given a contract to develop aerial refueling methods.

There was another, really odd reason why the He 177 was linked with aerial refueling: as a fast bomber, the RLM was hoping to use He 177s to intercept and shoot down aircraft making ferry flights from North America.

Junkers

Junkers was in the middle of developing the Junkers 290. While Marine scouting had been rolled into the design requirement early on, it was as a transport that the RLM was most interested in it, as the start of the war against the Soviet Union had sucked up all available Luftwaffe transport capability. The RLM heads also at a fairly early point identified the Junkers 290 as the ideal aircraft to become an aerial tanker in the refueling scheme just mentioned. In truth, it was: large lift capability combined with a long range would have made it the perfect utility airframe.

At no point though, now or later, did the RLM examine the bottleneck of production: the factory, based in Prague. In order to get the numbers the RLM really wanted, some way should have been found to expand the plant or build a new one. This is not a trivial point; as these posts continue, a constant theme is the RLM assuming production numbers without doing the work of expanding production facilities. In truth, this was a dysfunction endemic to the Reich. Having tapped all of its economic potential even before the war started, the Third Reich committed all of its military age manpower to the start of Operation Barbarossa; it now had no reserves left should anything go wrong with Hitler's all-in bet. Slavery of POWs had started with the invasion of Poland, and Operation Barbarossa would add millions more to be grist for the Nazi war mill. Fortunately for the Allies and the Soviets, you can't fix all your labor issues with slaves.

A surprise development for Junkers was that the RLM resurrected the EF100 project, to fill the transocean longer range recon role the Kriegsmarine was interested in. Work began again on the transatlantic aircraft.

Messerschmitt

Messerschmitt, who had personally done a lot to stoke Hitler's interest in ultra-long range aircraft, now found himself with another project the Reich was very interested in, furthermore considered it a vital priority to get series production of aircraft right away. The Me 264 promised Messerschmitt a chance to break into large aircraft, and secure a rare large aircraft contract from the Reich.

This was a mixed blessing.

On the one hand, more business for Messerschmitt, and an opportunity to fund RnD - good. Ernst Udet, RLM procurement head, had always been a fan of the Me 264, and wanted a production order of 3 prototypes with a production run of 30 aircraft to follow. The emphasis was on speed of deployment, to the point Udet flirted with the idea of concurrent development for the Me 264, a term that sends shivers down the spines of anybody who followed the deployment of the F-35. [What is meant by concurrent development is starting series production without a prototype series. You could argue the Nazis actually did that a fair bit in practice, as they frequently used prototype aircraft operationally, but the Me 210 had attempted this to hasten production, and the result was a bunch of unusable aircraft instead of a large production run of Bf 110s.] That said, Udet's thinking was not entirely without merit: assuming the Me 264 worked at all, it could at least perform reconnaissance of the North Atlantic.

On the other, Messerschmitt was at capacity in more than one sense. The Bf 109 and Bf 110 were essential war programs, but Messerschmitt was also working on the Me 210, the successor to the Bf 110, and that program had turned into a catasterfuck at least as bad as the He 177. It didn't really matter how important the Reich viewed the Me 210 - Messerschmitt couldn't get the damn thing to fly properly, with prototypes demonstrating such foul flying qualities test pilots were refusing to fly them. The Messerschmitt firm had also started flight tests of the Me 262, what would, of course, be the first operational jet fighter. So winning a contract for the Me 264 was a personal vindication for Dr. Messerschmitt, but also more work ontop of many other responsibilities. Messerschmitt had also promised Udet that the Me 264 could go from design drawings to a flying prototype in a year and a half?

|

| The initial prototype under construction. |

|

| The Me 264's cockpit with the pilot's seat removed. As you can see, the tube of the fuselage was not exactly spacious. |

|

| This shot of the initial prototype shows off the fuselage narrowness well; only a little larger than the engine cowlings. |

In addition to spare capacity problems (Messerschmitt didn't have any), the firm found itself so over tasked that some design work for the Me 264 had to be subcontracted out - the tail and the wings ended up being designed by Fokker in the Netherlands. There was a larger problem as well - calculations seemed to show the Me 264's radius of action was only 5000 km, half of Messerschmitt's [insanely ambitious] design goal of 10,000 km. In fact, math savvy doubters at the RLM had figured that Messerschmitt needed six engine to carry a five metric ton bomb load to the United States. (Messerschmitt started work on a six engined version of the Me 264 to counter these criticisms.) These matters were not helped by Messerschmitt and Milch [RLM production head] having a long standing grudge. Messerschmitt had always been obsessed with performance, even at the cost of safety. In the late 1920s, when Milch ran Lufthansa, a Messerschmitt design crashed, and Milch publicly blamed Messerschmitt taking too many engineering risks, a charge Messerschmitt hotly denied. There had been hostility between the two proud, strong willed men ever since. There was also a political dimension; Milnch and the RLM controlled Junkers much more directly than Messerschmitt, thanks to its own aeronautical-related anschluss. Milch preferred this project go to a company they had direct control over.

Dr. Messerchmitt, in the face of all this pressure, was obsessive about boosting the range of the Me 264, and got his development team to consider all sorts of ways to consider improving its range. In truth, this was a payload problem, and in turn, an engine problem. Payload in a aircraft is not only what cargo or ordinance it can carry, it is also the aircraft's capacity for fuel. Your payload is limited not only by structural limits of your aircraft, but your engine power. You can get further by adding more engines, but that of course adds more weight, and demands more fuel, so the best engineering solution is to have more powerful engines. As I've gone on some length about, this was a problem in the Third Reich. This was especially a problem when developing Amerika bombers, as the payload demands caused by the extreme range requirement were especially unforgiving. Designers like Messerschmitt tried to get around this by building aircraft that focused on low drag and minimizing mass, but there was only so much that could be done. In order to give it Amerika bombing range, Messerschmitt had already burdened the design with as much fuel as he dared; the Me 264 was calculated to have a preposterously long takeoff roll of 2 kilometers. In order to pack ever more fuel into it, the Me 264 design team began to look at alternate takeoff methods. These include rocket assisted take off, being towed aloft by a tow-plane, or mid air refueling (from another Me 264, naturally.)

At the end of 1941, Messerschmitt produced a 15 page booklet - a sales brochure, really - on the Me 264.

Using DB 603H or Jumo 213 engines, Messerschmitt envisioned varying ranges and payloads for his new airplane. He projected a range of 11,000 km with payload for the "long range" version, and a range of about 9000 km for the "heavy bomber" version. Messerschmitt envisioned payloads of 8.4 metric tons for the Long Range version, and 14 metric tons for the "heavy bomber" version. These ranges and payloads were - to put it kindly - optimistic, even assuming, as Messerschmitt had, the use of advanced and as of yet not in production engines. A B-24 Liberator in Very Long Range (VLR) configuration only carried 1.2 metric tons of bombs. A more apples to apples comparison would be to the B-32 Dominator, which managed a 9.1 metric ton bomb load, or the B-29's standard 9 metric ton payload. Messerschmitt had two further variants, a cargo/courier aircraft, and a pure reconnaissance version. Had the Me 264 seen even modest production in a more rational Reich, the cargo version might have been the realized variant, as now that trade routes were cut off from Japan, the Germans belatedly realized how vital their trade had been. The recon version, free from the weight of ordinance, was projected to have an endurance of sixty hours and a range of 20,000 km, easily spanning North America.

Speaking of courier aircraft, the Me 261 test flight program proceed without drama, accumulating some 40 hours flying time, though the DB 610s proved to be a source of trouble - the engines were sent back to the factory in the summer of 1941 to be rebuilt. A second Me 261 had been finished, and took flight in early 1941. Outside of the small cadre of flight test personnel, it seems to have been forgotten about in the preparation for the final war of total annihilation, or however Hitler was referring to it in the various genocide-planning symposia he kept hosting. This was also partially because the Me 261, a quasi-civilian design, lacked armored and self sealing fuel tanks.

Conclusion

I'm now wondering what kinda conversations I could eavesdrop on at the RLM around this time, had I been a protagonist in a sneaking video game like Dishonored or Deus Ex. I can't help but feel some of the RLM goons must have been having hushed conversations about how messed up the whole Amerika bomber fancy in fact was.

The RLM had stopped work in even prototypes of a Strategic bomber in the 1930s on the basis that Germany couldn't spare the capacity. Then, they decided to bet on technology getting around Germany's resource issues - as of late 1941, that program had yet to produce anything operational. Now, with war with the United States ever more likely, and a major opponent safe on their Island, their factories geared up for total war, Nazi Germany decides to take whatever conceivable slack remaining in the economy and attack the Soviet Union, redoubling the industrial strain. While in late 1941 German forces were surfing from victory to almost unbelievable victory in the Soviet Union, it was not hard to see the risk. If Germany couldn't defeat the Soviet Union, that was pretty much it. If the great gamble failed, it had no more manpower reserves, and the Third Reich would have most of the world's industrialized nations poised against it.

In the psychological context, I suppose, the Amerika bomber project makes perfect sense. The Nazis feared the material might of the United States, if only remembering what a thumb on the scale it had been during the last war. The Amerika bomber was a fantasy of striking back against the United States. The idea that strategic bombing could actually damage the North American economy made sense, but given the constraints discussed above, it could only be something pursued once the Greater German Reich was secured - if resources like oil or aircraft manufacturing capacity were too tight to build aircraft to support the U-Boats in the Atlantic, there was no way in hell anything like effective strategic bombing could have been commenced on a trans-Atlantic basis.

What had happened is that the Nazis had started a war assuming they would be short, and geared their armed forces as best they could toward that end. Once the war proved to be not short, instead of focusing on the opponents they had, they started a new fight with a new opponent, as they figured this new opponent would be the one to go down in a short, tactical war. This of course you, reader, know to be a cardinal mistake, the mistake, the thing that would crush the Third Reich like a festering anti-semetic pig carcass underneath a T-34's implacable steel tread. In a delightful irony, this fateful mistake was brought on by the racism of the Third Reich's senior leadership. Seeing the Slavic peoples as sub-human, they really did think a single German soldier could take on a thousand Slavic untermenchen and win, regardless of who had better supplies.

To get back to Amerika bombers, the push for Amerika bombers can be seen - despite Hitler's dreamy little dreams of the American eastern seaboard in flames - as a long term RnD project for when the Greater German Reich had the Caucuses oil fields and the Mideast. The fact that it was roped into the long suffering Kriegsmarine's desire for proper air cover in the west Atlantic was rather incidental. After all, U boats really didn't have proper air cover around the Eastern Atlantic yet. For that matter, British factories after 1940 were more threatened by submarine blockade than air attack. Moreover, General Walter Weaver, 1930s RLM strategic bombing enthusiast, thought specifically of those strategic bombers targeting Soviet factories beyond the Urals; the fact that Germany now had nothing to target them with does not seem to have caused much lost sleep in the RLM.

Well, maybe to Ernst Udet. He killed himself in late 1941, partially because of the swirling chaos of RLM procurement. His successor as RnD head was Ernst Milch, which must have given Dr. Messerschmitt a nasty twinge. One more thing happened in 1941: the Japanese attacked the Americans at Pearl Harbor, and a few days later, Hitler did the Americans the favor of making the state of war between them official. Amerika bombers were no longer just for daydreaming, as far as the Third Reich was concerned.

[note: I've no idea if Wiley Messerschmitt was in fact a doctor of engineering, but I've decided to just go with it as it makes it easier to distinguish between Messerschmitt the firm, and Messerschmitt the man.]

Part of the Amerika Bomber series.

Part 1: Black Gay Hitler

Part 2: Vague Plans and Flying Boats

Part 4: Stuffing arrogant mouths

Part 5: Eris is Goddess

Part 6: Ragnarocky Road

Part 6: Ragnarocky Road

Part 7: Look Busy and Hope Americans Capture You

Part 8: Rocket-Powered Daydream Death Notes